The Northwest Room is pleased to announce the newly published Christopher Petrich Photographs in ORCA. Christopher Petrich was born in Tacoma and attended Bellarmine High School, Georgetown University, and the American University in Washington DC where he studied art, design, and art history. He also studied under fine art photographer Alan Ross. Petrich began his career at age sixteen as a Photographer and Lab Technician in the portrait studio of Bert Perler. In the early 1970s, he sold cameras at Barney Elliot's Camera Shop in downtown Tacoma.

He was hired as a Photographer by the City of Tacoma where he worked with William Trueblood and Jerry Timmons to photograph city events. He worked on a number of aerial photography assignments in this role and performed darkroom lab processing for the City. He photographed notable Tacoma visitors including Leroy Ostransky, Jacques Cousteau, Bill Cosby, and Richard Nixon and he created visual documentation of the Hawthorne District which was removed during the construction of the Tacoma Dome. In 1985, Petrich and Jerry Timmons founded Image Market Studio on 6th Avenue. Over the course of his career, he was employed by the Weyerhaeuser Company, the Washington State Legislature, and Yuen Lui Studios. His work has been exhibited widely across Washington and shown in Colorado, California, and Vermont.

The Northwest Room asked Mr. Petrich about his development as a photographer and the background on a few series of photos in his collection. Below is a portion of that interview. To read the full interview, click here.

At the age of 16 you started working as a photographer and lab technician. From then on you worked in a wide variety of jobs in the photography field. In what ways did these many different types of photography jobs shape your skills?

Each place presented a different set of challenges based on what the business delivered. For example, Perler’s studio was focused on in‐studio portraits, but made its money in the high school Senior Portrait business. As a high school sophomore, I took a camera to football games and school functions chiefly to supply pictures to the school yearbook. This Perler provided for free as an incentive for the school to give him the senior business. That meant that I had little to learn, since I was doing that anyway as a student at Bellarmine. Perler, and Harta as his chief competitor, followed the same playbook. I found that my professional skills depended more on my relationships with individuals working in these various businesses, who would show me the ropes on the technical side, and share their favorite tricks. The greatest influence on the job came from Jerry Timmons at the City of Tacoma. Jerry learned photography in the Army, and he was really good at simplifying things so that they worked without much risk. He created a negative filing system that depended on date and a sequential number on an envelope stored in a bank of custom wood drawers. It was a good system because it simplified searching for negatives shot in the past. I use the same system today.

Bruce Bleckert ran Custom Photo Service from the basement of the Pantages Theater, with the entrance on Commerce Street. He took a special interest in me as a young photographer, but I was not the only one he helped that way. His business was exclusively black and white processing and printing, and his specialty was called “inspection processing,” where he would look at the film while under a very dim Green safelight half way through development and make adjustments based on what he saw. The most profound influence, aside from my parents, was Pat Twohy, a teacher at Bellarmine. I worked on the school paper as photographer using a Polaroid Model 180.

I worked for other businesses too, Yuen Lui Studios, Maarten and Strode, and Barney Elliott’s Camera Shop to name three. Finally, the best teacher for print quality has been Alan Ross of Santa Fe. Alan was Ansel Adams lab assistant for 5 years, and Adams chose Alan to print the Trust negatives after he ceased doing it. When I spent time with Alan in his Santa Fe darkroom, my printing took an immediate jump in quality. I thought I was good, but I learned so much from him in such a brief amount of time. Photography is a constant effort at improving my technical skills, and once acquired, that expertise can be lost without practice, or through shortcuts, or laziness. I have a good eye, but photography is a harsh taskmaster. It will flunk you if you slack off. I have proof of that from even my latest work. But when the rare, good picture comes, I am seduced. I want to make more.

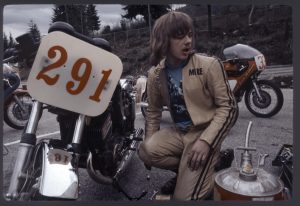

Can you give us background on the series of motorcycle racing images in your collection?

I was working for Perler at the time. There was a young woman there whose boyfriend rode, and it was she who invited me to Seattle International Raceway (SIR) to shoot. I thought there might be money in it, selling prints to the riders, so I went. I learned though that the riders were young, poor, and interested in putting money only into their bikes. There was no money for pictures. I was trained as a photojournalist so I made sure I covered the event well, including establishing shots, shots of the riders and the organizers, and shots of the race. It was a time‐trial race, so there were no head‐to‐head contests, and the weather was cold and damp. I didn’t know at the time that the event was a first ever road‐race organized in the weeks before. That makes the photos important, documenting the beginning of organized motorcycle road racing in the Pacific Northwest. Once it was clear that there was no money in it, I abandoned the effort and left the collection to sit in my files for fifty years until I reviewed them recently.

Were the portraits of Ella Carter on her 100th birthday taken for her and her family or for another project?

Back then, it was rare for anyone to reach their centenary birthday, so it was an important event. I think by then Ms. Carter was alone. I know she lived alone in that old house. An historian who asked me to photograph the Hawthorne District, Doug McDonald, also got me to make pictures of Ms. Carter. She was tiny, less than 5 feet in height, but she carried herself with grave dignity. One photograph shows her seated in a large chair in her front room, dwarfing her in size. She sits on it as if on a throne. After I made that formal portrait, Doug and I stood outside while she regaled us with stories from her front porch. Her expressions and her mood shifted suddenly and dramatically while we spoke to her. It wasn’t for long, just a few minutes, but I’ll never forget it. I think one of my shots was published by the city in a monthly newsletter.

Can you give us some background on the Hawthorne neighborhood photographs? Were the images for a personal project or were you hired to take them for a client?

Doug McDonald and his wife, Kathy Fox, were friends when he came to me with his research on brewing in Tacoma. I had no idea, but he had found that Tacoma was a brewing hub in the late 19th and early 20th century before prohibition killed it. Doug was passionate and knowledgeable, and overwhelmed us with the details of his research as we talked about it in our living room over beer. I knew brewing was big in the past, because it was easy to see the large painted advertising signs for Alt Heidelberg beer and Carling, among others. When I was young, my parents were friends with one of the Carling Brewing executives. Doug really anticipated the craft brewing movement by decades. I wasn’t that invested in it. I liked drinking single malt more that beer. I remember one day Doug showed up telling me it was urgent to go down to the Hawthorne district to attend a community meeting so I could photograph it, to make a record of this effort to save the neighborhood before it was bulldozed into the ground. I was not aware of it, but I knew there was a good story in the struggle against authority. I also knew that their struggle was well‐covered by local media, and that my pictures would not be published in the news. Nevertheless, I went down there several times to get shots of the houses on the street, children playing, the old beekeeper with his protest sign, and the 4‐plexes being moved. Once the neighborhood was flattened and the dome construction began, Jerry Timmons asked me to help him make aerials construction progress photographs. Jerry’s tenure with the city ended when he left to start Image Market Studio with me on Sixth Ave. We flew aerials of the Dome construction as part of our Regular Aerial Photographic Service (RAPS) promotion. We were both pilots, and for weeks would alternate who would fly and who would shoot. So, I was on both sides of it, seeing the removal of a viable, if powerless community by authority, and having fun flying with my good friend.

Now that your collection is online and accessible, what do you hope people take away from these photographs?

I asserted from the beginning that these images are valuable for research into the city’s past. Most of the pieces are records rather than important aesthetic photographs. My hope is that they provide a look at the city when I was living here, to help understand how we all got here. Tacoma has from its beginning been a magnet for photographers, and I like standing with them. My parents were active supporters of the Tacoma Public Library. I know they would be proud that my work would be included within the Northwest Room collections.

Click Here to explore the Christopher Petrich Photographs in ORCA.

To visit his online journal, Click Here

We hope you enjoy this newly available collection! If you have any questions, please reach out to us at nwr@tacomalibrary.org or by phone (253) 280-2814.