This is a guest post by Andrew Weymouth an archivist, digital media editor and exhibit designer working in Tacoma, WA. He was the recipient of the 2021 Visual Resources Association Foundation grant, the University of Oregon's Vollstedt program and the University of Washington's Storytelling Fellows. He has created digital exhibits for Indigenous higher education reform, Middle Eastern graphic novels and Tacoma architecture. His previous writing focused on displacement, settler colonialism and oral history have been published by Archival Outlook, Library Juice Press and The Serials Librarian.

I had heard about the Tacoma Mountaineers Scrapbook collection since I started working with the Northwest Room more than a year ago and was very excited to have a chance to make these records accessible to Tacoma Public Library patrons. The organization, which was formed in 1906 and sprouted a Tacoma chapter in 1907, offers a unique glimpse into progressive era ideals, a budding environmentalism movement and Tacoma’s relationship to nature right on the heels of the closing of the Western frontier.

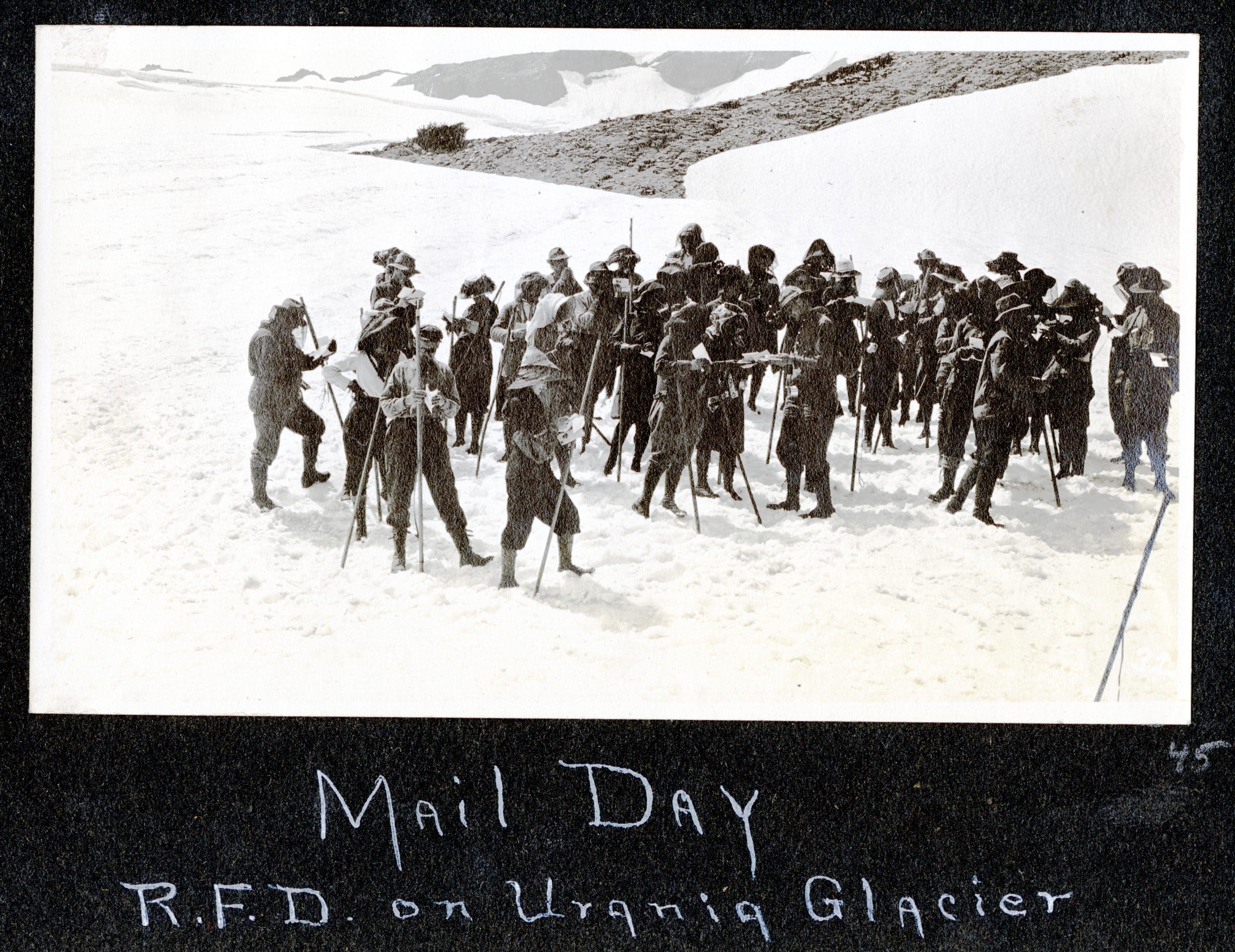

The scrapbook I worked on, which spans 1912 to 1916, visually documents several "outings" organized by the Seattle and Tacoma chapters and records notes that range from simple places and dates to elaborate poems. The mystery of the album is that there is no plain identification of an author, although we have a few clues. In the 1912 Mountaineer, the club's periodical, we can see one of the photos from the scrapbook credited to an H.V. Abel within an article by E.M Hack describing a 10,000-foot climb from Glacier Basin to the summit of Mount Rainier.

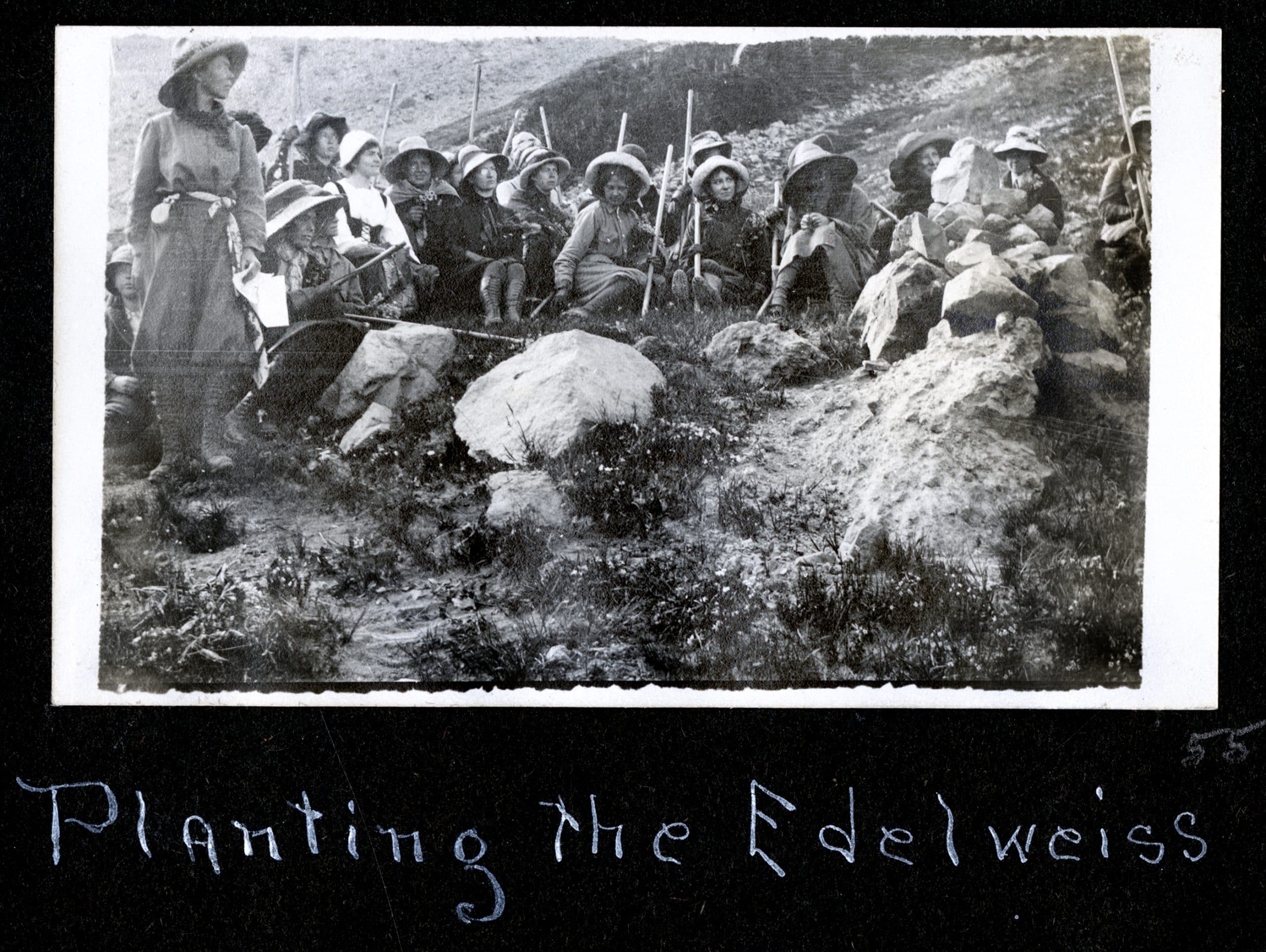

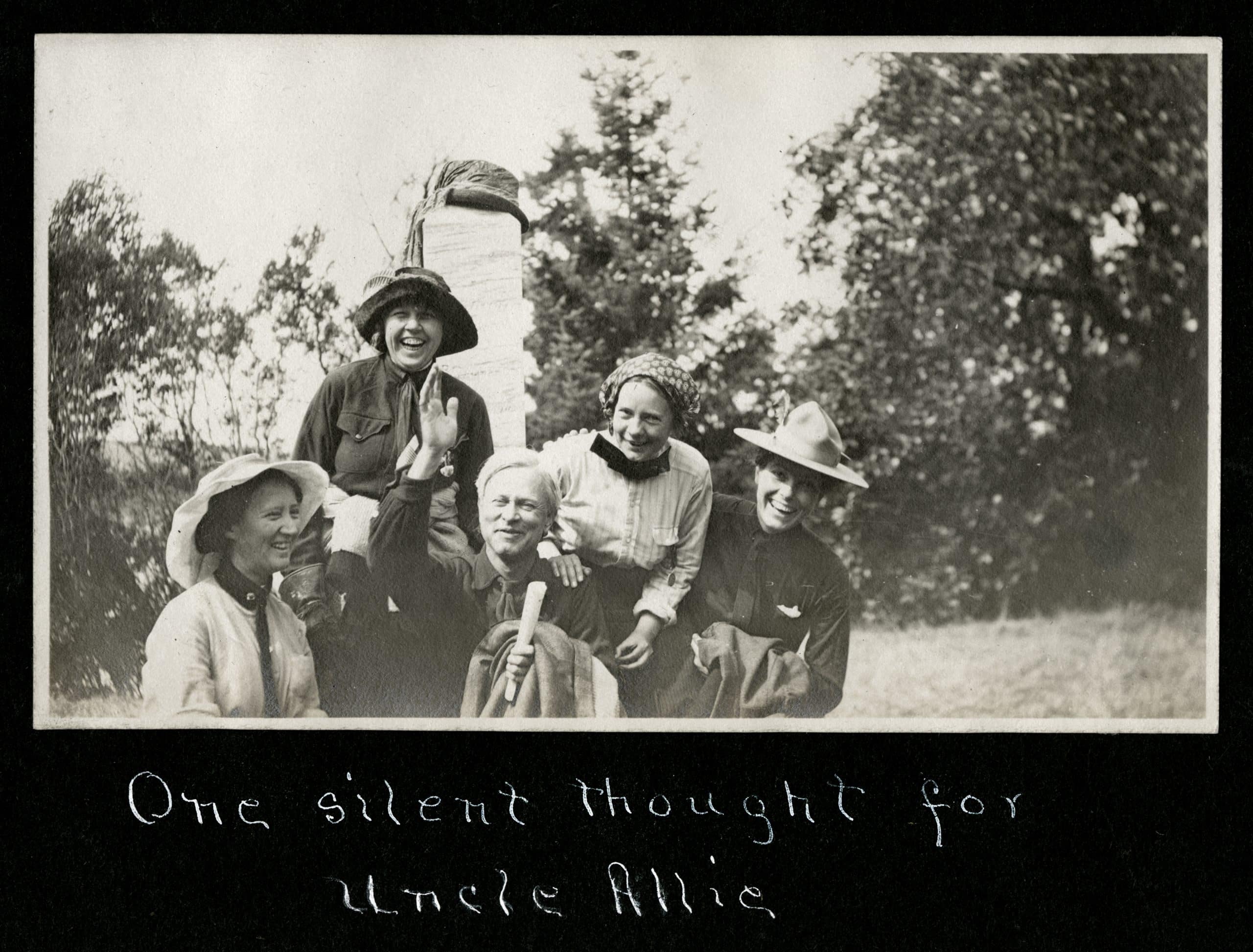

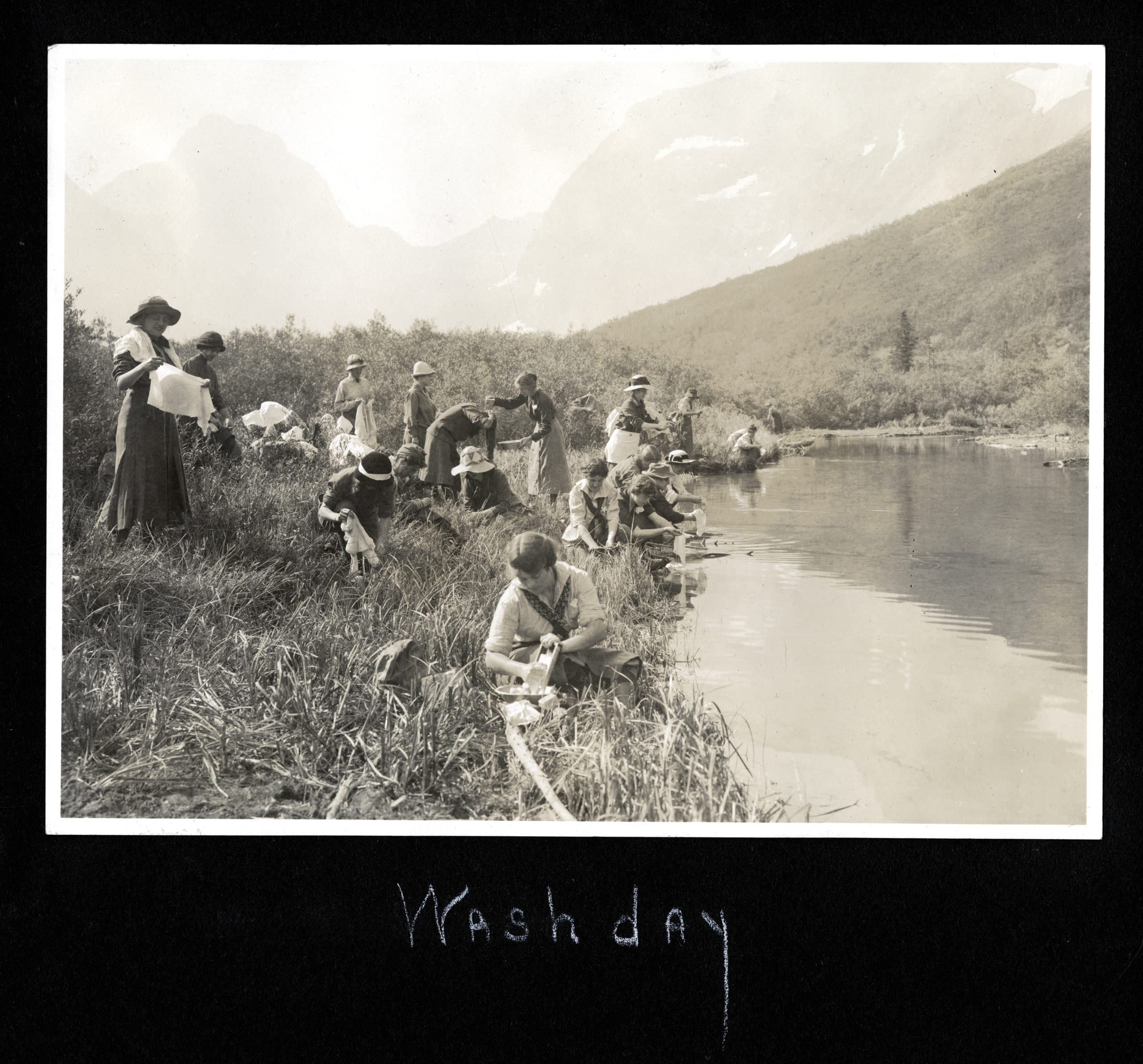

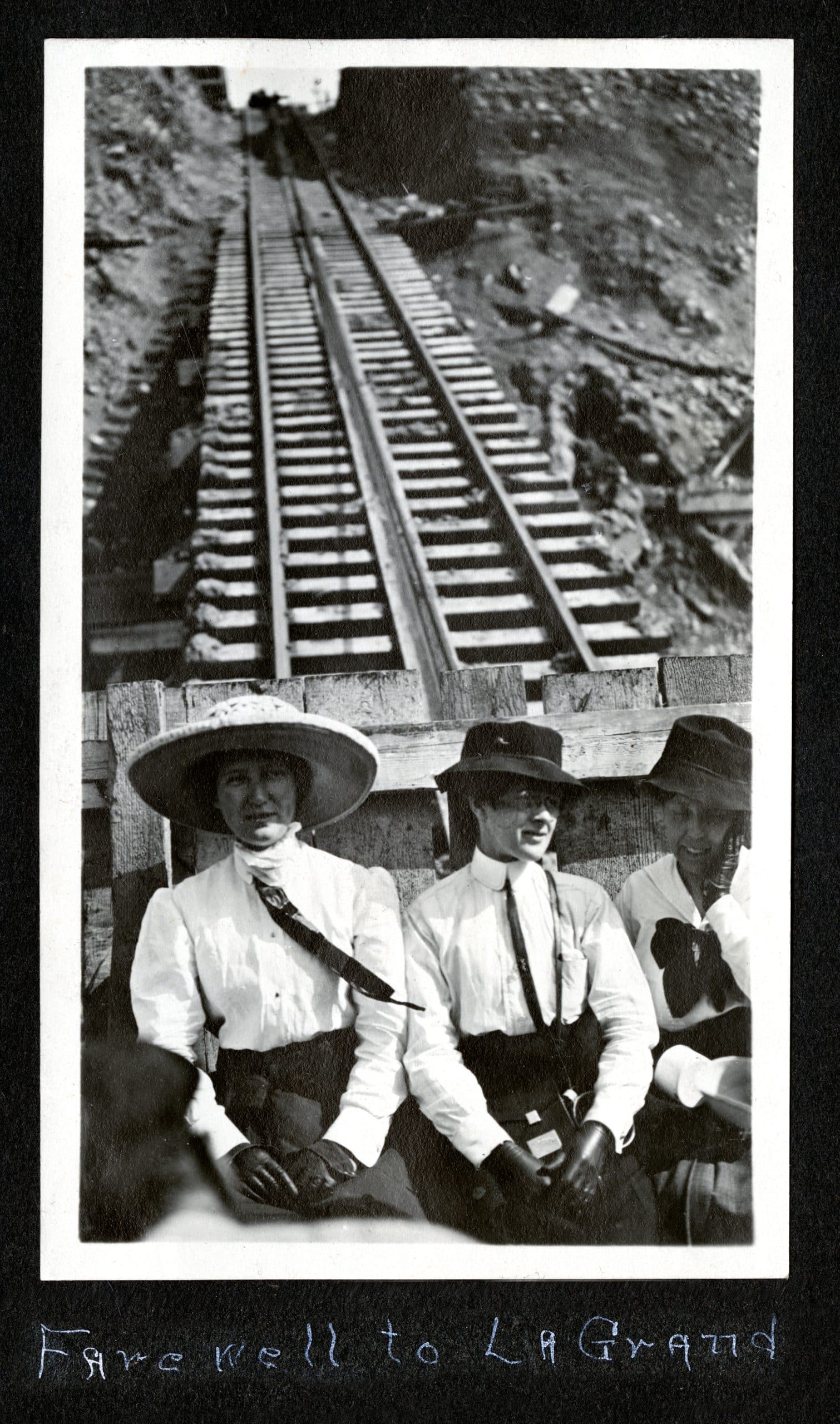

While the author could be Hack, Abel or any of the other nine Mountaineers recorded present for the outing, I would be very surprised if it wasn't one of the many female members of the club. In contrast to the photographs in public-facing Mountaineer, which often featured men staring out upon epic vistas or ant-like profiles hiking into vast glacial caves, the photos in the scrapbook are candid, human-scaled and occupied by a majority female Mountaineers.

Similarly, in the introduction to the 1912 Mountaineer, the author notes the higher purposes of the club being environmental and scientific, while a less explicit ideological through line of the organization were women's rights. Many of the members were teachers in Tacoma area schools (possibly the reason for the Lincoln High School collage towards the back of the album) and may have been involved in the incredibly popular Women's Club movement happening in Tacoma during this period. In 1909, to pledge their support of suffrage advocates visiting the state for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the Mountaineers hung a "Votes for Women" pennant from the summit of Mount Rainier during a 1909 expedition.

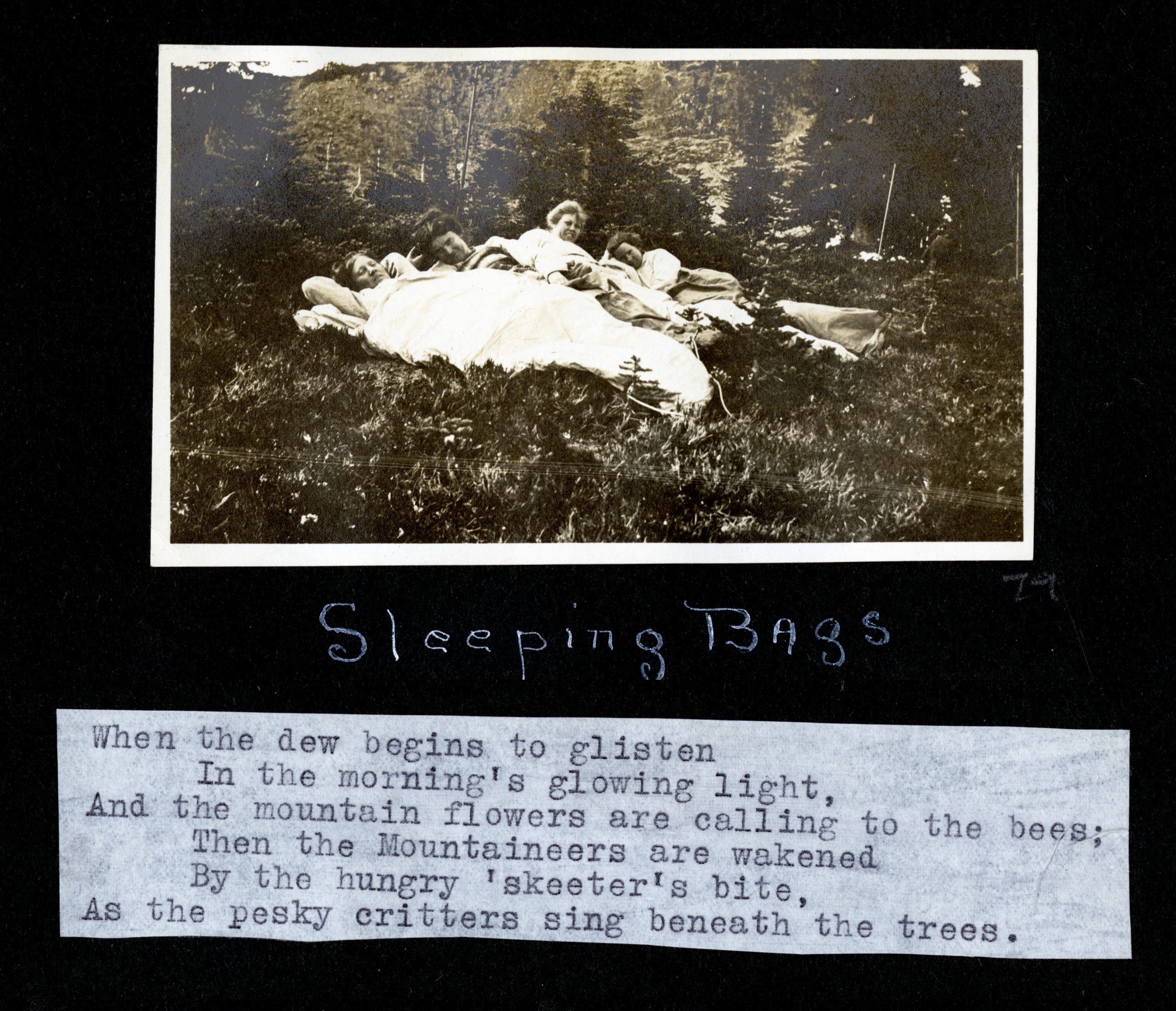

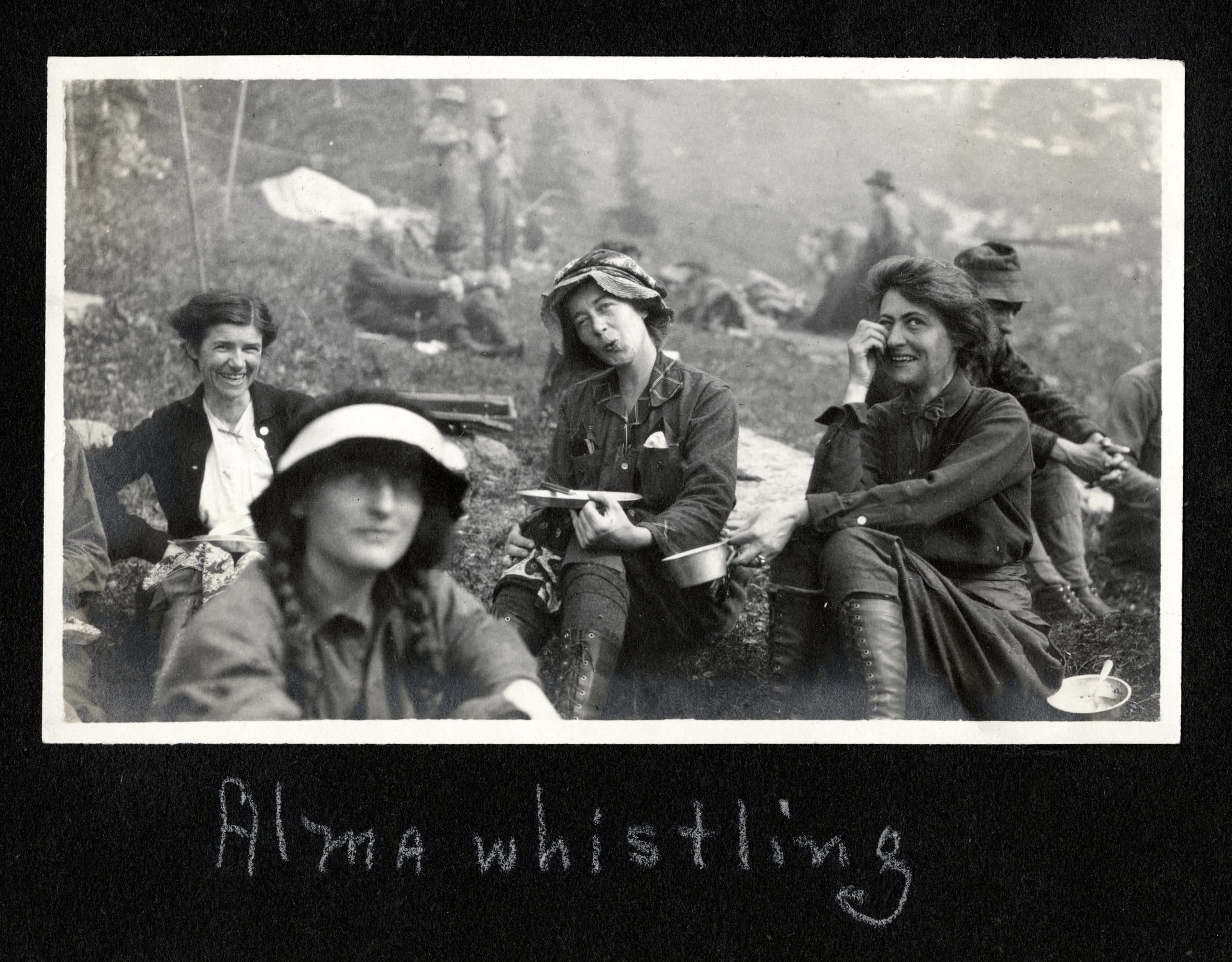

This progressive, independent focus is reflected in the photographs that appear in the scrapbook. Groups are pictured smiling groggily in sleeping bags, washing clothes in glacial rivers, waiting for breakfast and annoying each other with whistling around the campground.

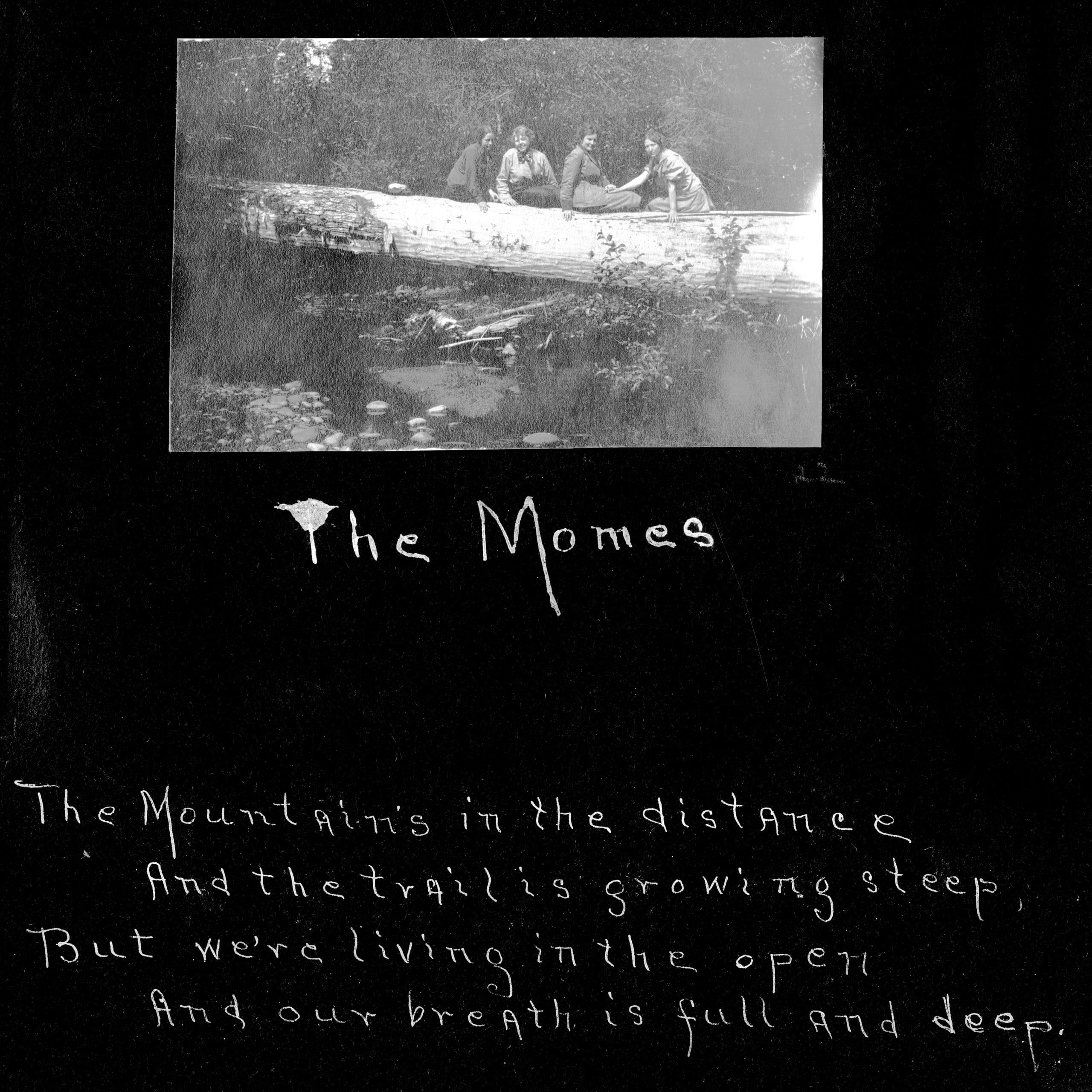

Subcultures within the Mountaineers are hinted at with the author identifying a small group as "The Momes," an archaic term that means a fool or blockhead, also 'kid', in French. The word mome also appears in Lewis Carrol's Jabberwocky ("all mimsy were the borogroves, and the mome raths outgrabe"), which might explain the author's penchant for writing similar "nonsense" style verse of the era.

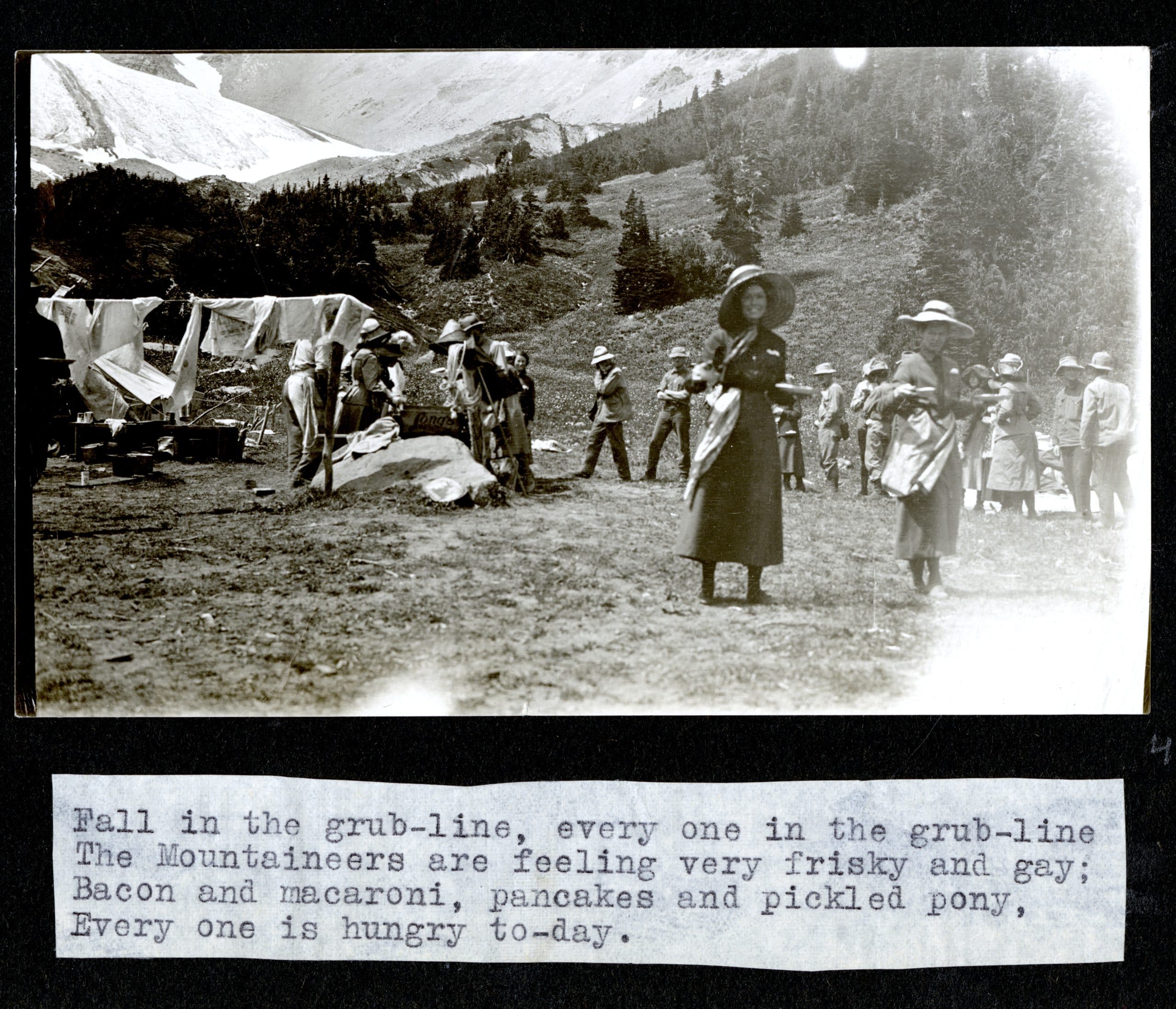

Below a photograph of the group in line for breakfast, the author wrote:

"Fall in the grub-line, every one in the grub-line,

The Mountaineers are feeling very frisky and gay,

Bacon and macaroni, pancakes and pickled pony,

Everyone is hungry to-day"

Other poetry in the scrapbook was originally penned by Edmond S. Meany, professor of botany and history at the University of Washington and president of The Mountaineers since 1908. The cultural importance of verse is also reflected in the annual Mountaineer Songbooks, which may have been inspired more generally by the late nineteenth century nature poetry movement, notably led by Emily Dickinson.

This collection offers a unique insight into Tacoma culture in the turn of the century, how they connected with the nature of the Puget Sound and how that connection with nature reflected the independence and autonomy Mountaineer members were seeking outside of the organization.